My Wednesday series, fulfilling a long-standing promise to

and hopefully extending some horizons here and there. Many of these biographies I haven’t read for several years, so these posts will be sign-posts or lamp-posts more than… err… the sort of posts you drive into the ground when you want them to stay there for ever.A serious hat-tip to My Journey Through the Best Presidential Biographies.

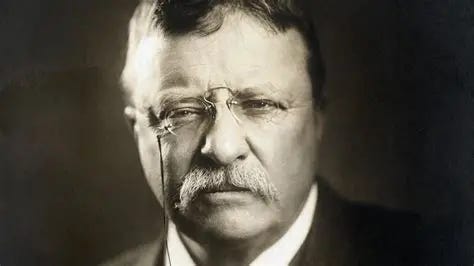

Theodore Rex, Edmund Morris

Theodore Rex is quite a funny title at this particular moment, given the ‘No Kings’ demonstrations throughout America (which is BS, by the way: nearly everybody would be happy with a king, so long as he did what they wanted). Roosevelt, still the youngest president in history, was by no means a king but he was a disruptor. A Progressive Republican, he was prepared to wield a big stick against previously settled concerns, notably the great industrial concerns that he ‘trust-busted.’ And he also won a Nobel Peace Prize. He hymned the values of physical activity alongside intellectual development and is definitely worth reappraising as a role model. A remarkable man.

The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft and the Golden Age of Journalism, Doris Kearns Goodwin

This isn’t a biography of Taft but a rather unwieldy tome that tries to cover the three subjects in the title. It does this very well but could and perhaps should have been two books. The ‘Golden Age of Journalism,’ according to the author, is one of dedicated, honourable seekers after truth… well, ok Doris, but William Randolph Hearst? Roosevelt remains fascinating and poor old Taft, who was a public servant par excellence, is rather lost as he was lost in the shuffle of history. He was a wise and under-rated president, later Supreme Court judge, who deserves a decent biography of his own.

Wilson, A. Scott Berg

Speaking of presidents who wanted to be king, Wilson had been a professor at Princeton whose studies led him to conclude that the Constitution was inadequate, with too many checks and balances, and that the Executive needed more power – in order that it could use its power for good, obviously. This allowed him to lock up Socialist Eugene Debs, who would be released by (Republican) President Harding. In Britain and in this book, Wilson is portrayed as the noble idealist whose desire for peace was undermined by ignorant rubes in the Senate. The book is too one-sided to be so long; if you take Berg at his word, the New Testament reads as an early and inadequate rehearsal for Wilson’s life.