About twenty years ago, when I was idly pursuing graduate studies at Yale and incidentally proving that the one major qualification for acquiring a PhD is Not to Die, I wrote a fortnightly column for the Yale Daily News. This attempted to set new standards for being innocuous as I strove to avoid even mildly irking anyone, ever, or passing any comment on anything on which anybody could possibly disagree. (And these were the days when Yale students were relatively sane).

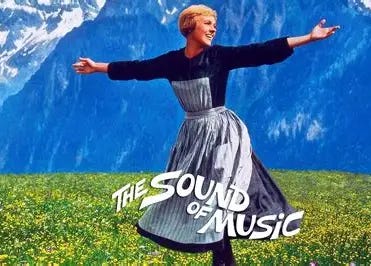

When The Sound of Music came to New Haven, then, it was the ideal subject. As I wrote at the time, the success of The Sound of Music was such that I could say “high on a hill stood a lonely goatherd” and be confident that 99% of people would respond “yay yodelay yodelay-ee-hoo!” The other 1% are probably the sort of people you don’t want to know.

There are people who sneer at The Sound of Music. Admittedly it loads the dice: on one side, a feisty yet loveable young woman and some (supposedly) adorable children; on the other, the Nazis. Not much dramatic conflict there. “Reactionary shit,” scoffed Time Out, in one of the laziest reviews ever written, sniffing that the film regarded a woman’s place as in the home. (It is possible that Time Out has dismissed other films as “radical shit” or “feminist shit” but somehow I doubt it). As with a great deal of Rodgers and Hammerstein, the female lead character in Sound of Music is more interesting, stronger and more independent, than the lead male. It staggers me that Time Out couldn’t see the character and narrative arc of Maria through anything other than its own peculiar filter, but that’s what comes of ideological capture.

More seriously, musical-theatre people don’t rate The Sound of Music as first-class R&H and are mildly peeved that the film made it far more successful, better-known and with more cultural purchase than Carousel or South Pacific. The film does help; no matter how cynical and grumpy one happens to be, it’s difficult not to enjoy. Even the kids are bearable, despite Robert Wise’s direction that they react to Julie Andrews’ every quip with implausible levels of amusement. (Robert Wise there giving the lie to Nominative Determinism). Friedrich is meant to be fourteen, for heaven’s sake; where are the scenes of him stomping around Salzburg with his hands in his pockets muttering ‘this is all bullshit’?

The main criticism is that Rodgers and Hammerstein, the great innovators, had simply run out of steam. It’s not that The Sound of Music is bad, exactly, it’s merely good. The songs are by-the-book; literally so, in that they are impossible to present (and certainly impossible to act) without Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse’s book. Their libretto is better than you think, by the way, and for which Crouse plaintively asked to be given some credit for the success of the show. It may even be the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical that deals most obviously in archetypes. Even so, it was a touch extreme of the distributors in South Korea to shorten the film by cutting all the songs.

But the songs have entered the language. Every so often in class I would say “let’s start at the very beginning” and usually some child would complete the line, to my great delight.

The slight problem with ‘Do-Re-Mi’ from my point of view is that, without a bit of practice, I can’t actually distinguish do from re. It has been suggested that Hammerstein’s lyrics for the solfège are weak (“la, a note to follow so”) because they are exactly what you’d expect from an improvising nun, but if musical theatre accepts the convention of people bursting into song at all it should credit them with some talent. (This is why Sondheim’s retrospective criticism of ‘I Feel Pretty’ annoys me - if you’re going to have a Puerto Rican girl burst into improvised English song, I don’t see why you can’t give her a decent rhyme scheme). Douglas Adams suggested that ‘la, a note to follow so’ was a dummy lyric that Hammerstein either forgot or didn’t bother to change, which seems plausible given his - Hammerstein’s - state of health.

In the original show, which opened on Broadway in November 1959 and ran to June 1963, ‘Do-Re-Mi’ was sung by Maria on her introduction to the children. (Maria was played by the star of South Pacific, Mary Martin, who was frankly getting a bit too old to pass as a postulant). In the film, as you know, it became an extended publicity shot for the city of Salzburg. I spent four days in Austria in February 2022 and my time in Salzburg was about as happy as I expect to be this side of the grave, not merely because I was replicating Do-Re-Mi as far as possible.1

I also visited Nonnberg Abbey, which is like the perfect Venn Diagram for my interests: history, Catholicism and musical theatre. It was something of an effort to remember that the nuns in 1937, whose graves lay before me, probably weren’t asking how they could solve a problem like Maria. It always struck me as an odd song, although there’s no particular reason why a group of nuns shouldn’t act as any other female community chorus; it’s a very Hammerstein idea and nuns are thoroughly real people, after all.2

I’ve even heard her singing in the abbey…

Hammerstein’s nun lyrics are more bothersome in ‘Climb Ev’ry Mountain’ and ‘My Favorite Things.’ The latter was moved in the film to replace ‘Lonely Goatherd’ in the storm scene, but in the show it is sung by Maria and Mother Abbess before she leaves the abbey for the first time. It’s the sort of lyric that adds a mental asterisk to Hammerstein, as though he’s writing Hammerstein pastiche:

“Raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens”

But whiskers aren’t ‘on’ kittens in the same way that raindrops are ‘on’ roses. Ok, fine, maybe it’s just clever use of the language, but why only cream-colored ponies? why not chestnut? why doorbells, for heaven’s sake? why rhyme ‘eyelashes’ with ‘sashes’ when the stress falls on the first, not the second, syllable of eyelashes? and are you seriously telling me that, when the dog bites, you conjure the image of bright copper kettles?3

And ‘Climb Ev’ry Mountain’ is clearly this show’s You’ll Never Walk Alone; a would-be stirring anthem of courage, self-worth and commitment. But, and call me picky if you wish, a Catholic abbess would never have chosen these words:

“Climb every mountain

Ford every stream

Follow every rainbow

Till you find your dream

A dream that will need

All the love you can give

Every day of your life

For as long as you live”

A non-denominational Mother Earth figure with a belting soprano, yes. But not an abbess.

Patricia Neway was the original Abbess on Broadway. Somebody once wrote that Ed Sullivan wore the faintly uncomfortable expression of a man who feared a hand on his shoulder at any moment.

Despite the down-draft from the helicopter knocking poor Julie Andrews to the ground, the film greatly benefits from taking the opening scene to the Alps rather than the theatre. ‘The Sound of Music’ is nearly tautological - for what is the sound of music other than music? - but Hammerstein has enough poetry in his soul to weave a spell of faint religiosity that avoids nature-worship only by referring it to music, the great human universal that is, somewhat ironically, both before and beyond language.

“My heart wants to beat like the wings

Of the birds that rise from the lake

To the trees.

My heart wants to sigh

Like a chime that flies

From a church on a breeze,

To laugh like a brook when it trips and falls

Over stones on its way

To sing through the night,

Like a lark who is learning to pray.”

The anthropomorphic heart again. “And how,” queried Mark Steyn, “do you tell a lark who is learning to pray from one who’s learned?”

The helicopter problem accounts for the awkward cut as Julie starts to sing. If you’re going to find God in the beauty of nature, you’re as likely to do it in Salzburg as anywhere.

I’ve never liked ‘So Long, Farewell’ largely because of my aversion to anything designed for children to show off,4 but ‘The Lonely Goatherd’ is fun as Hammerstein channels Lorenz Hart:

“Men in the mists of a chapel dote heard”

- at least, that’s what allmusicals.com wants you to think, clearly defeated by the unusual vocabulary of “men in the midst of a table d’hote heard.”

I don’t know why this version appeals so much; after all, I don’t speak Norwegian. Perhaps it’s because it so clearly shines with the sheer joy and lack of cynicism that can and should be preserved by theatre; not always by any means, but at least sometimes.

Ethan Mordden defends Sound of Music against its critics but calls it the “only unsurprising show” of Rodgers and Hammerstein with “the most detachable numbers” of any score. But surely the songs in Sound of Music are wedded to The Sound of Music? Yes indeed, but for the most part they’re not crucial to the plot and that’s what he means by detachable. Perhaps that’s what they were thinking in South Korea.

I’ve mentioned before, and could go on at length about, the importance of well-regulated masculinity in The Sound of Music. Rolf has the right idea in ‘Sixteen Going on Seventeen,’ assuming the role he is as yet too young to play, but betrays it for the corrupt masculinity of the Nazis. Only Maria can enable Georg to show Friedrich ‘how to be a man,’ which he demonstrates in the final scenes. In fact, and this may be why it fundamentally works, The Sound of Music is about well-regulated loves: of God, both within and without the abbey; of the beloved, each of whom will grow through the love of the other; of the family and of country. Which brings us to what may be the best, or at least the most moving, song from The Sound of Music - a fact that itself demonstrates the strange alchemy of musical theatre. After all, what is it? a few bars and less than forty words about a flower.

‘Edelweiss’ was, famously, the last song Oscar Hammerstein ever wrote before he died. Theodore Bikel, playing Georg, happened to be a decent folk singer and could thus accompany himself on the guitar.5 The song expressed his patriotism in the face of the daemonic race-worship that was trying to drag him into the Navy of the Third Reich; so effective was ‘Edelweiss’ that, also famously, it has been taken as a genuine folk-song and indeed the Austrian National Anthem.6

You don’t need me to tell you that the flower is a symbol, pointing beyond itself not only to the homeland - the same homeland that has been singing ‘for a thousand years’ - but also to the rightly-ordered loves for which he is about to defy the Nazis. It is so supremely fitting that this should have been the very last word from the Master of Simplicity himself:

“Edelweiss, Edelweiss

Every morning you greet me

Small and white, clean and bright

You look happy to meet me

Blossom of snow may you bloom and grow

Bloom and grow forever

Edelweiss, Edelweiss

Bless my homeland forever.”

If you didn’t know Christopher Plummer was dubbed for the film, I can only apologise.

Photos of Salzburg from the author’s collection!

For the best nun novel, read Rumer Godden’s In This House of Brede.

The counter-argument would be that Hammerstein is writing for an ingenuous young woman with limited life experience; rather like Sondheim’s self-criticism of ‘I Feel Pretty,’ in fact. Up to a point, Lord Copper… I refuse to believe this is the best Hammerstein could have produced.

Which is why Musical Mondays is unlikely to cover Annie or Matilda.

People ‘remembered’ Edelweiss in much the same way as they would ‘remember’ Tomorrow Belongs To Me from Cabaret.

Enjoyed this essay so much - thank you. Now I'll be humming Edelweiss to myself all day - happy background music to my day.